The design story of the Seagram Building, 375 Park Avenue, New York City, built in 1957

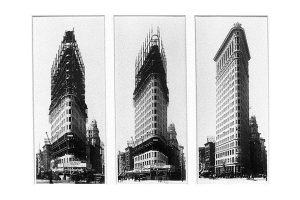

Built in 1957 the 38 story Seagram building designed by van der Rohe hailed in the Modernist style to the US and set the standard for office towers around the world. Photography by Noroton.

Delving into the roots of the building’s modernist design

Functional/Modernist architecture was a style of design that first emerged through the Bauhaus movement founded by Walter Gropius in Germany in 1919. The design innovations commonly associated with Gropius and the Bauhaus—the radically simplified forms, the rationality and functionality, and the idea that mass production was reconcilable with the individual artistic spirit—were already partly developed in Germany before the Bauhaus was founded. The original modernist buildings were typically industrial. The Fagus shoe factory, constructed in 1911 in Alfeld on the Leine,Germany is considered by many to be the first modernist building in the world. Designed by Walter Gropius and his partner Adolf Meyer the Fargus building has been designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. In this beautifully simple building, you can already see the roots of future modernist skyscrapers, including the Seagram Building.

Mies van der Rohe subsequently took over from Gropius in 1930 before the school in Berlin was closed in 1933 by the rising Nazi regime. When the staff reluctantly emigrated from Germany the ideas of the movement began to spread like wildfire in Europe and America. In 1937 Mies van der Rohe moved to Chicago where he was appointed head of the department of architecture at the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT)

How Modernist principles blended into American architecture

At the turn of the twentieth century a first Chicago School of architects were among the first to promote the new technologies of steel-frame construction in commercial buildings, and develop a spatial aesthetic which evolved in parallel with European Modernism. It led to the construction of a number of high-rise buildings both in Chicago and in other cities across the US. However these tall buildings still kept elements of neoclassical architecture such as cornices and bay windows projecting out onto the street (oriels). The work of Mies van der Rohe amplified this modernist movement which played a seminal role in shaping modern American architecture right up into the 1970s.

During his academic and professional experience Mies van der Rohe had selectively adopted ideas from Russian Constructivism for “efficient” sculptural assembly of modern industrial materials. Van der Rohe also picked on the ideas of the Dutch De Stijl group in the use of simple rectilinear and planar forms, clean lines, pure use of color, and the extension of space around and beyond interior walls.

His early projects at the IIT campus presented to Americans a style that seemed a natural progression of the almost forgotten nineteenth century Chicago School style. His architecture, with origins in the German Bauhaus and western European International Style, became an accepted mode of building for American cultural and educational institutions, developers, public agencies, and large corporations.

It was Phyllis Lambert, the daughter of CEO and owner of Seagram Samuel Bronfman who commissioned the Seagram Building on behalf of the Canadian spirit brewer, Joseph E. Seagram & Sons.

A flagship project for the design of office buildings worldwide

The Seagram project was Mies van der Rohe’s first tall office building, and his design set the standard for office towers around the world. It was designed by Rohe to look elegant and to demonstrate the wealth of the owners very clearly. For this flagship project he left aside the modernist principles of using cheap mass-produced materials to build the most expensive tall towers at the time. Upon its completion in 1958 the building costs amounted to $41 million. That was a colossal amount which equates in today’s money to around $328 million. A large proportion of that budget was spent on the building’s interior design which included lavish materials such as granite, marbles and bronze.

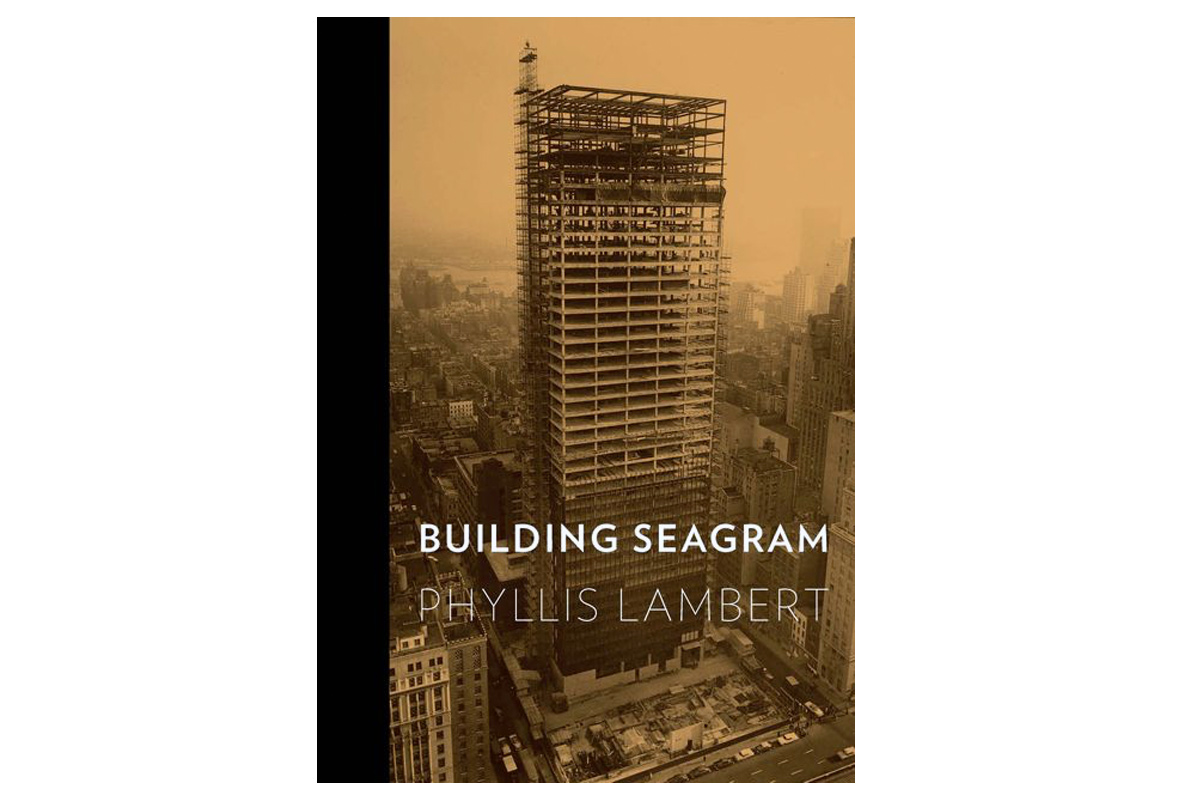

This photo of the Seagram Building, taken in December 1956, under construction reveals its steel and concrete structure (cover photo of the book “Building Seagram” by Phyllis Lambert)

This 38-story building 515 feet tall (157 meters) has a typical steel structure combining a steel moment-resisting frame with a steel and reinforced concrete core for lateral stability. Poured concrete is used to make up the floors while concrete core shear walls extend up to the 17th floor. Further diagonal core bracing (shear trusses) extends to the 29th floor. Van der Rohe also specified bronze outside the building which enhances the grey glass used in the curtain wall. Although the bronze seems to be a structural component when you look at the building from outside in actual fact, its purpose is purely decorative.

A lasting legacy for modern urban planning

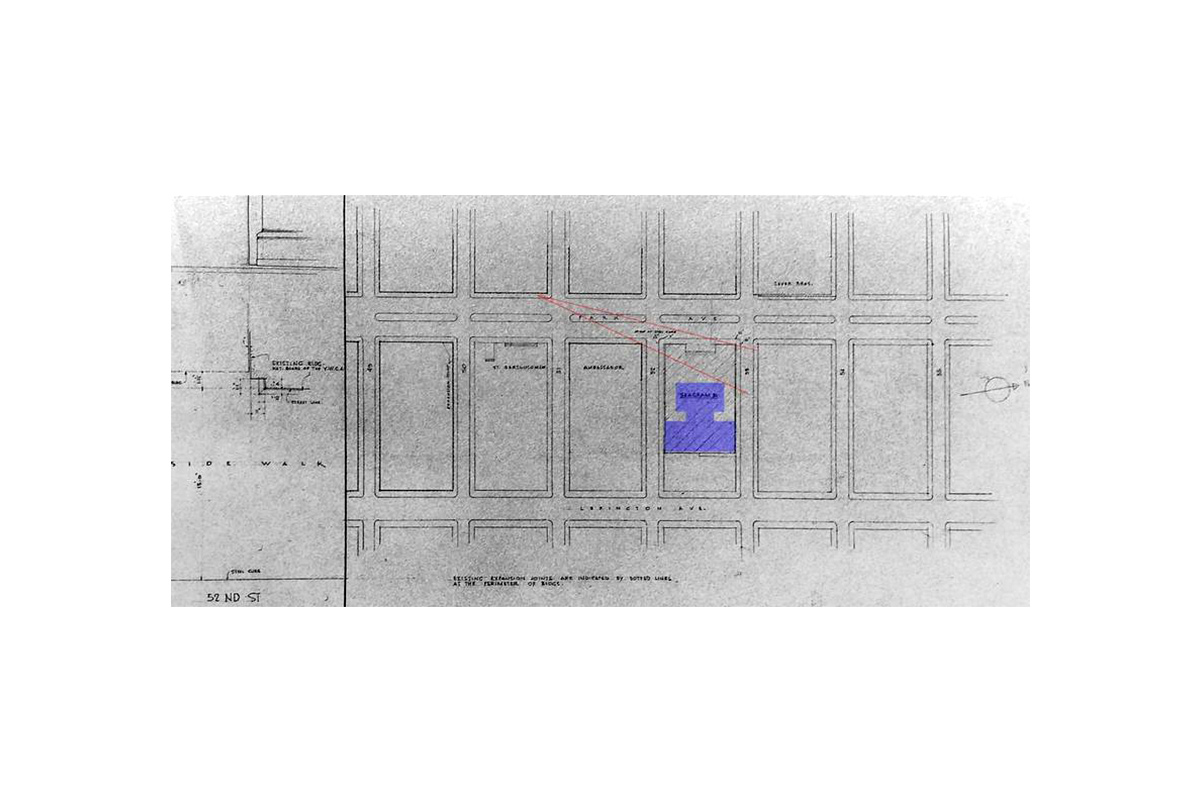

Another distinctive feature is how the building was placed within the construction area. Whereas most contemporary buildings used the whole building plot, Van der Rohe set his client’s building back by about one hundred feet from the road. This decision completely overturned the financial modelling in skyscraper construction. Setting structures back from the street made the built environment friendlier for city dwellers. They freed up land surface for a plaza or public open space and allowed the streets below to gain natural daylight.

This original site plan shows that by setting the Seagram building back from the street and using only part of the building plot Van der Rohe created a precedent that was to mark US urban planning thereafter

Set back from Park Avenue, van der Rohe created a large, open granite plaza which remains a very popular gathering area to this day for office workers in NYC. There is also a set of fountains to highlight this iconic building which was bought in 2000 by Aby Rosen, the West German-born property investor for $375 million.

In 1961 the city of New York was enacting a review of its zoning laws. It brought in incentives to allow developers to include privately owned public spaces into their projects. This new zoning directive builds on the successful experience of the Seagram project. Over the years it has led to the creation of new plazas and landmarks throughout NYC such as The Hudson Yards, where Thomas Heatherwick built in 2019 The Vessel, an extraordinary structure of connected stairs in the shape of a honeycomb. To conclude the Seagram building has left a lasting legacy both in architecture and urban design.