The Flatiron Building (originally the Fuller Building), designed by Daniel H. Burnham and built in 1902

Even if you haven’t yet travelled to NYC you will not fail to recognize the unmistakable triangular shape of the Flatiron Building which has featured in countless blockbuster movies such as Reds, Godzilla, or Spiderman.

Aerial view of the Flatiron building at the corner of Fifth Avenue, Broadway, and East 22nd Street. Although this triangular prism resembles the shape of a clothes iron the building derives its name from the Flatiron District neighborhood in Manhattan.

This 22-storey, 285-foot (86.9 m) tall steel-framed building is located at 175 Fifth Avenue in Manhattan, New York City. The name for the building has nothing to do with its metal structure but comes from the Flatiron District neighbourhood where it is located.

The Flatiron District rests on an area of Manhattan where its schist bedrock is deepest underground and as a result under the influence of zoning laws, the tallest buildings in the area could reach 20 storeys.

The building was designed by Daniel H. Burnham who was a pioneer in the development of skyscraper building and design. He founded the architectural practice, Burnham and Root with his friend John Wellborn Root in 1873. Burnham is considered by many to be ‘the father’ of the skyscraper.

Burnham and Root had previously designed The Montauk Building, a ten storey high steel commercial block which was constructed between 1882 and 1883. Although the building was demolished in 1902 to make way for the First National Bank headquarters there are claims that the Montauk was the first building to be referred to as a skyscraper. It cost around $325,000 at the time , about $8.3 million in today’s money.

Designed as a vertical Renaissance palazzo

Using the lessons learnt on projects such as The Montauk Building, Burnham set about designing and constructing the Flatiron Building which was originally called the Fuller Building in honour of George A. Fuller a Chicago based architect and real estate developer. The latter had expanded his business to the NYC marketplace and is often credited as being the “inventor” of modern skyscrapers. However, NYC locals persisted in calling the new tower block “The Flatiron” a name which has since been made official.

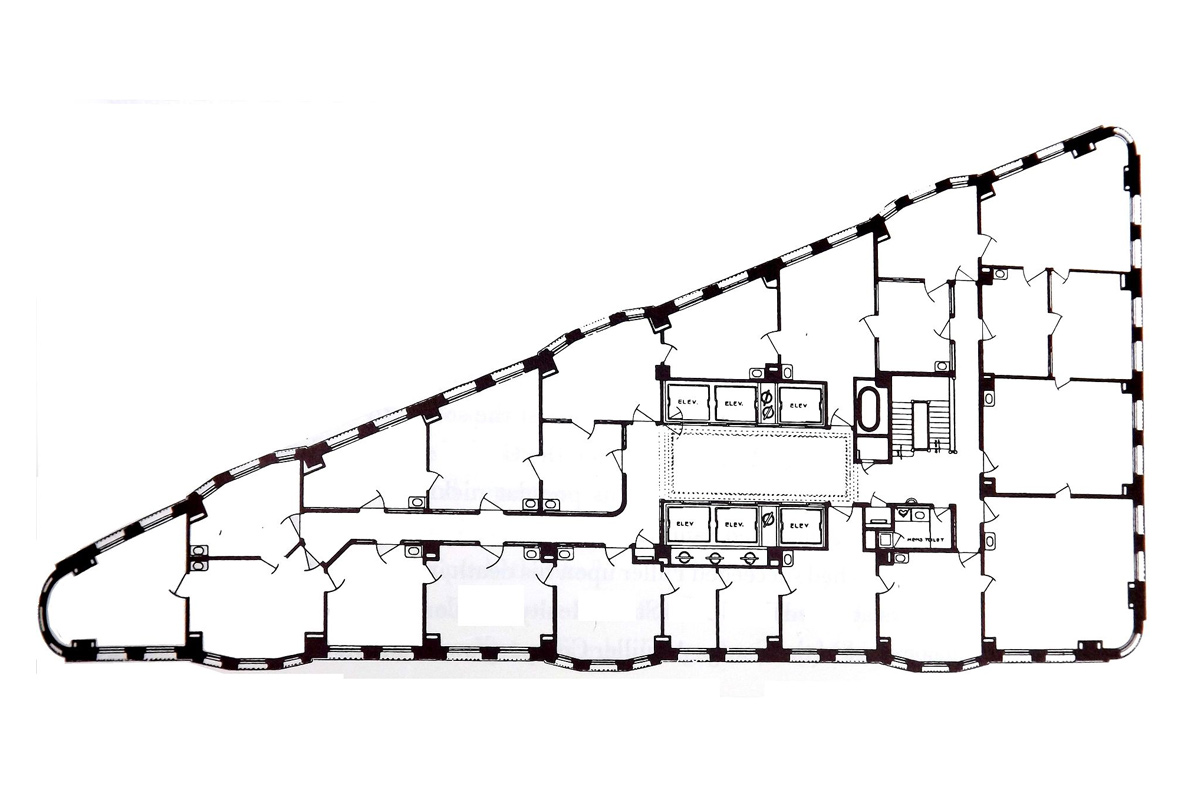

The rather abstract triangular shape of the building was governed by the layout of the plot owned by Harry S. Black, George Fuller’s son-in-law who had taken over the Fuller Company. The layout forms a triangular prism around an almost perfect right angle triangle so that the building is only six feet wide where the two longest sides of the building meet. The building’s design stems from the Beaux-Arts school of architecture, a relatively short-lived movement that started in 1895 and lasted around 45 years. The buildings designed in the Beaux-Arts school are all characterised by symmetry and include lots of design elements, such as balconies, pilasters, balustrades etc. The Beaux-Arts school was also very fond of Italian and French renaissance influence so Burnham designed the building as a vertical Renaissance palazzo.

Behind the ornate facades lies one of NYC’s first steel skeleton structures

The building contains a skeleton of steel, and the building’s frame was clad with limestone and terra-cotta curtain walling. Like a classical Greek column, its facade is divided into a base, shaft, and capital with limestone at the bottom changing to glazed terra-cotta as the floors rise,

The architects used the then-revolutionary curtain wall method. This method took advantage of a change to New York City’s building codes in 1892, which eliminated the requirement that masonry be used for fireproofing considerations. This opened the way for steel-skeleton construction.

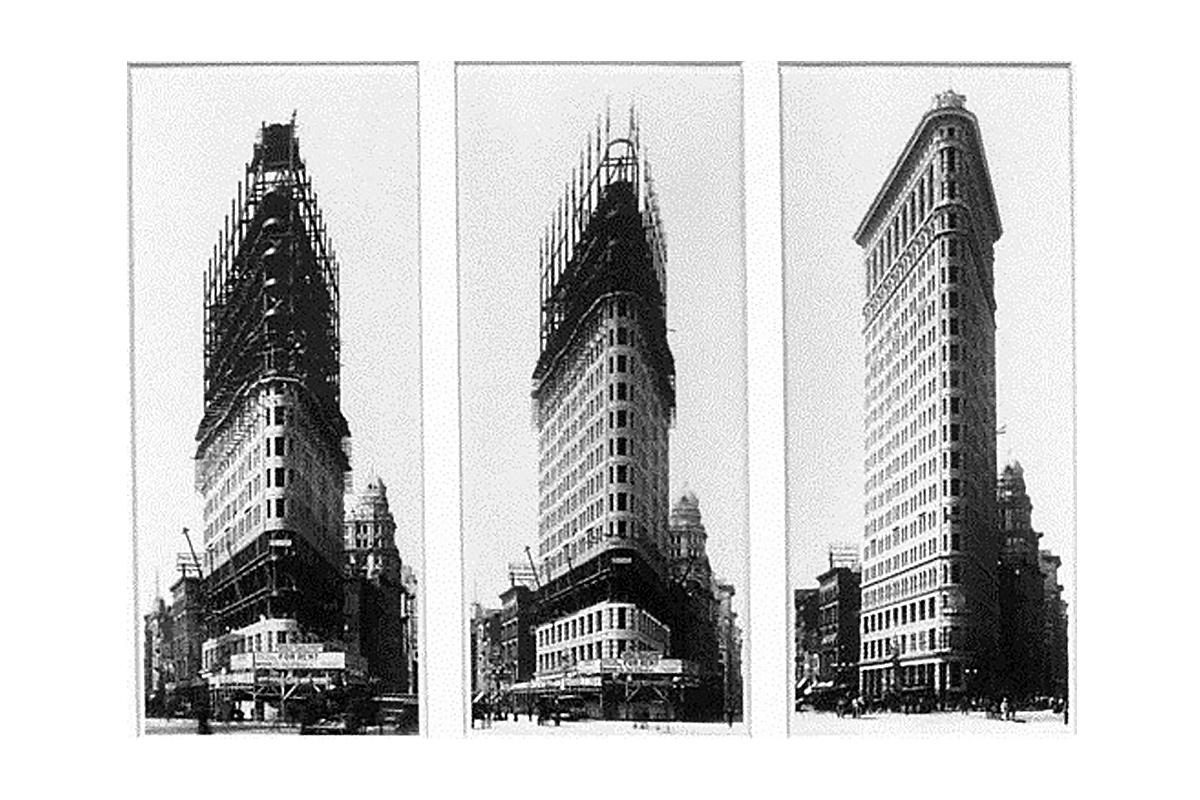

Once construction kicked off in the summer of 1901 the building went up at an amazingly fast pace of one floor a week. All the steel parts were meticulously pre-cut off-site and slotted together very quickly. By February 1902 the frame was complete, and by mid-May the building was half-covered with terracotta tiling. The Manhattan neighbourhood watched on in awe as this giant Meccano was put together and completed in just one year by June 1902. The 20- story high steel-framed building topped out at 307 feet tall which made it one of the tallest tower blocks in NYC at the time.

These images show the different construction phases of the Flatiron building: first the steel frame structure followed by the limestone and terracotta envelope (159 words)

Image from the Library of Congress

On completion, many leading experts expected the expectation the building might blow over in the first strong wind. But Purdy and Henderson, the building’s structural engineers had anticipated this problem: since the building was quite narrow and therefore had less volume to resist wind load they strengthened the structure. Steel bracing enabled the building to withstand four times the amount of wind force which it could ever be expected to endure. In 1905, three years after completion it was decided to add a penthouse level at the top of the building as well as a basement floor so that made a total of 22 floors. A retail space at the front of the building (dubbed as a “cowcatcher”) was also added in order to maximize the use of the building’s lot and produce some retail income.

The building’s novelty attracted a flow of criticism

As so often happens with iconic buildings, its design was not popular with architectural critics, and The New York Tribune memorably described the building as ‘a stingy piece of pie.’ The New York Times described it as ‘a monstrosity.’ The original owners moved out of their 19th floor home in 1929 and although the mayor of NYC tried to turn the area into a new business district, north of Wall Street this idea never worked. So for many years the surrounding area remained underdeveloped.

The office space within the Flatiron building was cramped and awkward to furnish because of its triangular shape. The architects also ‘forgot’ to include female restrooms

Because of the triangular shape of the structure, office space was extremely cramped and awkward to furnish. Tenants described it as a “rabbit warren” of oddly-shaped rooms.The building was considered to be “quirky” overall, with drafty wood-framed and copper-clad windows, no central air conditioning, a heating system which utilized cast-iron radiators, an antiquated sprinkler system, and a single staircase should evacuation of the building be necessary.

Despite its many shortcomings the Flatiron became very trendy

The building’s elevators were an Otis water-powered hydraulic type. This first generation of elevators were remarkably unreliable and extremely slow. Part of the problem was that the elevators were famous for leaking and flooding the building. The original and beautiful elevator cars are still in use to this day.

To make things worse, Burnham forgot to install or more likely did not install female restrooms. This omission meant that the building’s management had to alternate floors for male and female bathrooms. Additionally, to reach the top floor – the 21st, which was added in 1905, a second elevator has to be taken from the 20th floor. On the 21st floor, the bottoms of the windows are chest-high.

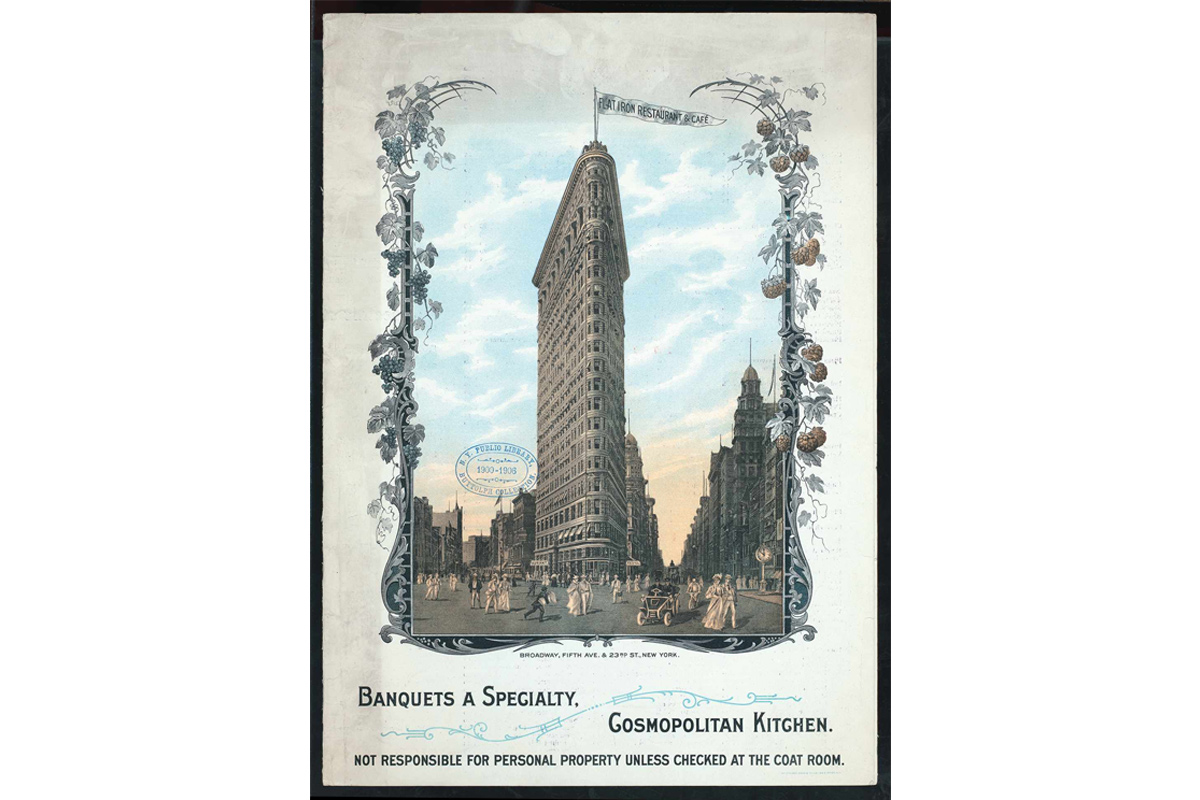

Despite all its shortcomings the Flatiron has attracted over the years an eclectic variety of tenants going from the prestigious Imperial Russian Consulate, to the crime syndicate Murder Inc. during the Prohibition period in the 1920s-30s. In 1959 Macmillan the publishers occupied the entire building between 1959 until 2004. The retail space (or”cowcatcher”) at the “prow” of the building was leased by United Cigar Stores, and the building’s vast cellar, which extended into the vaults that went more than 20 feet (6.1 m) under the surrounding streets was occupied by the Flatiron Restaurant, which could seat 1,500 patrons. In 1911 the Flatiron Restaurant was bought by Louis Bustanoby, of the well-known Café des Beaux-Arts, and converted into a trendy 400-seat French restaurant, Taverne Louis.

A massive basement restaurant in the Flatiron building attracted Broadway audiences, artists and jazz musicians.

It was conveniently open from breakfast through late supper to attract the audiences of nearby Broadway shows. It was among the first of its kind to allow a black jazz band to perform, thus introducing ragtime to affluent New Yorkers. However The Taverne was forced to close during the period of the Prohibition which led it to become a shady speakeasy during that period.

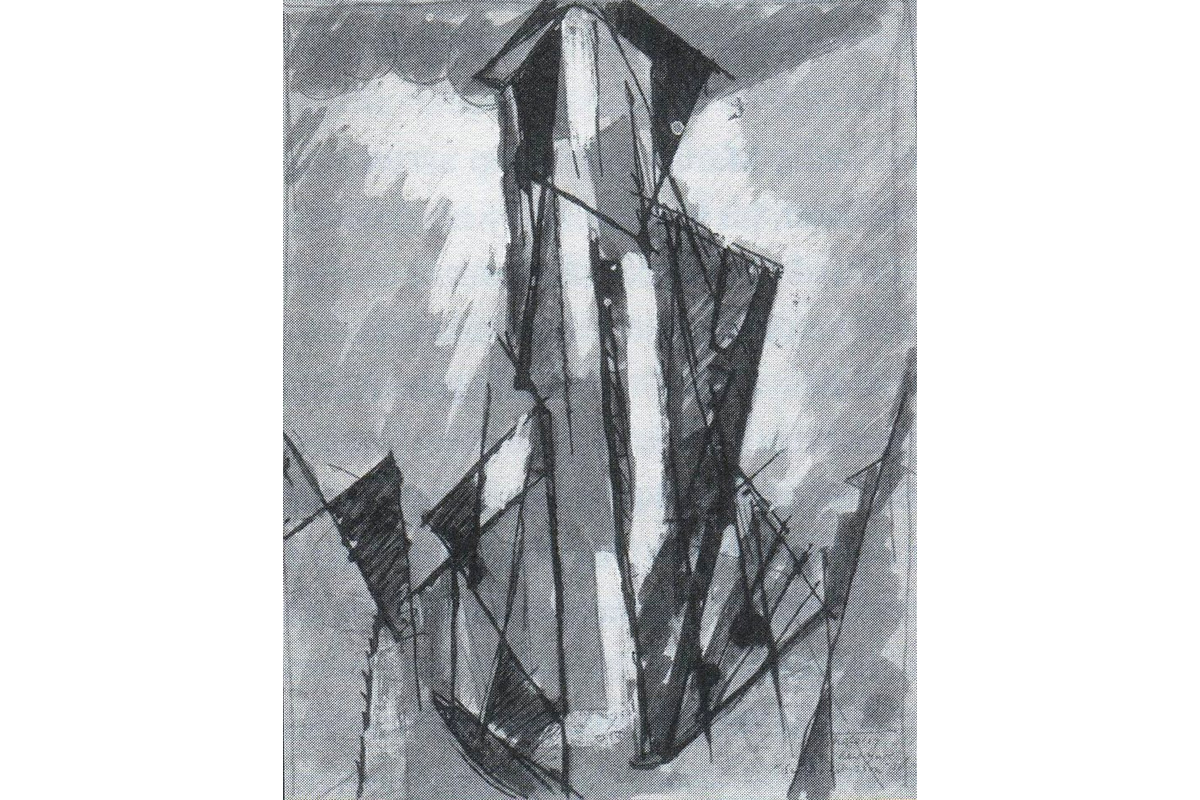

The Flatiron also attracted the attention of numerous artists such as the French artist Albert Gleize who made a Cubist style etching of the building in 1916. While taking a photo of the building during a snowstorm in 1903 the photographer Alfred Stieglitz fell under its spell “…it appeared to be moving toward me like the bow of a monster ocean steamer – a picture of a new America still in the making”. He added that the Parthenon was to Athens what the Flatiron was to New York.

“Sur le Flat-iron”, graphite, ink and gouache by Albert Gleizes, 1916 held in the permanent collection of The University of Michigan Museum of Art. Following its completion the Flatiron building inspired many artists such as this French Cubist painter.

As the building’s enduring appeal to New Yorkers grew, it helped to attract high-end shopping and fantastic restaurants. The Flatiron Building was designated a NYC landmark in 1966 and a National Historic Landmark in 1989.