22 Bishopsgate – The emerging of a vertical city for the 21st Century in the middle of the Square Mile

City of London

The City of London has seen its skyline change dramatically over the past two decades. Long gone are those pictures where one could only see the lonely Tower 42 designed by Richard Seifert signalling the location of the Square Mile in the horizon as if it was the lighthouse guiding the boats up the River Thames.

For those not familiar with the planning process in London and City of London in particular, it could be surprising that a number of skyscrapers have amalgamated within such a reduced portion of land, creating what planners refer to as the Eastern Cluster.

Several factors can explain this phenomenon. First of all, the development plan identifies this area as being able to accommodate a significant growth in office floor space and employment as well as being appropriate for tall buildings. The clustering of tall buildings in this area responds therefore to an attitude from the City of London to enhance the image and its skyline while minimising the impact or extension of the whole transformation.

City of London in the early 2000’s.. We can observe Tower 42 designed by Richard Seifert and Partnersonly accompanied by the Gherkin designed by Foster + Partners.

Saint Paul and the Viewing Corridors

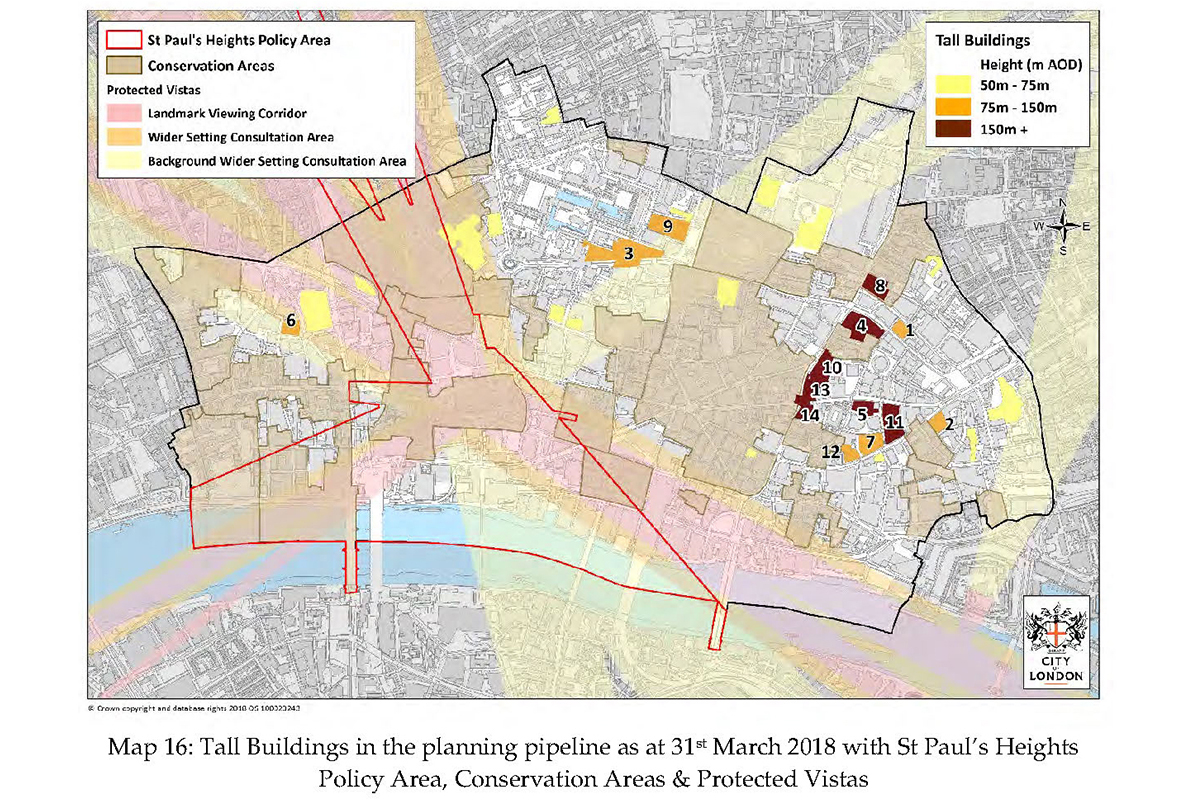

Besides the intention of The City of London to change its skyline there is another factor to take into account to explain the concentration of tall buildings in this area, and this is the protection of the views towards Saint Paul and its dome.

The vistas towards Saint Paul and other strategic landmarks are protected by the planning authorities. The reason for such restriction lies in the necessity to control or preserve the image and identity of these important buildings within their context because of their relevance and significant contribution to the image of London at a strategic level. Nothing that obstructs or undermines views towards these buildings can be built within the boundaries of the so called viewing corridors.

Tall Buildings in the planning pipeline as at 31st March 2018 from Tall buildings in the City of London Part 2, Published by The City of London Corporation; Department of The Built Environment on September 2018.

The Pinnacle, the Economic Crisis and the new commission

Back in 2007 planning permission was granted for a very ambitious scheme that embodied the flamboyant design trends of the time. Such design consisted of a 278m high spiralling tower named The Pinnacle. A short time after, the construction work started. Thus the three storey basement with its foundations and pilings were built followed by the construction of 7 levels of the central core before the economic crash happened. At this point in 2012 works were halted and never restarted again.

Time passed and it wasn’t until 2015 when a prestigious London developer purchased the plot from the previous owner with the intention to build a different skyscraper, more in line with the spirit of the time post-recession. This meant that the design had to reflect a synthetic solution advocating for sobriety and elegance over exuberance and spectacle in order to make the project economically viable for development.

Computer generated image of the design developed for the Pinnacle in the City of London neighbouring the Tower 42 designed by R.Seifert and Partners in the 1970s. Image source via Wjfox2005

Office standards had changed after the crisis and tenants had different requirements so it made total sense to develop a new scheme that could satisfy them. The Pinnacle design catered for a ratio of 1 occupant every 12m2 and after the crisis, tenants were demanding higher density office space thus the new design had to be able to host 1 occupant every 8m2. This meant a 33% of population increase within the building and this in turn, meant that the internal infrastructure of the building had to expand to cater for this population increase.

The greater number of lifts needed became a key factor in the design of the new project. The existing core designed for the Pinnacle proved incapable of providing sufficient service for the tenant’s latest and increased demands. Therefore, it seemed reasonable to demolish and start from scratch. The new scheme was designed trying to reuse as much as possible of the already existing Pinnacle’s basement levels and foundations. This challenge has its implications later on when designing the new structure, and it has shown in the latter design in the form of a series of inclined columns and transfer structures.

One of the biggest transfer structure in the design of 22 Bishopsgate, nicknamed by the design team as the “Rhino truss” for its geometry. It was required in order to transfer the loads from the south east corner columns of the building to the foundations that needed to be utilised from the old Pinnacle design.

Photograph by: Diego Padilla Phillips – Structural Engineer.

The new massing

During the design process, architects go through a series of massing studies and iterations for discussion with planners and developers alike in order to find an optimum design solution that respects the planning conditions and satisfies the client’s aspirations. It has become apparent that the new design for 22 Bishopsgate prioritises standardisation and repetition over singularity and exception.

This strategy not only maximizes the potential return of investment but also to be more environmentally respectful by minimizing the façade area. A minor façade surface not only implies reducing cost but it also allows for a less significant interface between the indoors and the outdoors, reducing the potential energy exchange hence complying with one of the basic principles of sustainability.

Left: Typical 3D printed models produced during the design process by OMA while finding the optimum massing to achieve both the client aspirations as well as meeting the planning requirements.

Right: Computer-generated image of the final design for 22 Bishopsgate inserted within the urban environment, the different height of the steps at the top of the building vary according to the surrounding circumstances.

The Vertical city concept

The 22 Bishopsgate building claims to create a community where people can not only work but also enjoy their spare time. Nowadays companies compete fiercely in a battle to attract the most talented people to work for them and the classic concept of office space has become obsolete.

The new building aspires to become a focus of activity within the City of London, a place which is also infamous for being empty dead during the weekends. It wants to be a point of attraction that can create a social hub out of office hours and that allow companies to attract the most brilliant professionals in the market to join them.

To achieve this, the proposed strategy intercalates zones for different activities at intermediate levels and intertwines art and architecture in the lobbies and around the ground floor in general. Level 2 will be a Food Court that will remain open to the public on the weekends and after 6pm on weekdays after the employees leave the workplace. Level 7 will offer an Innovation Hub for new Tech Start Ups to flourish. Level 25 will include a Fitness Centre. Level 41, the Retreat, will accommodate Spa, Sauna and Wellness Centre, Reading area, Yoga classes and so on. The cherry of the cake, which is always at the top, is the Level 58 Public Viewing Gallery together with the Bar and Restaurant split between Levels 59 and 60, where everyone will be able to enjoy a panoramic view of London from nearly 300m of height. Time will tell if all the intentions of the project become a success and cover the needs of the increasing competitive market and the complex society which we live in.

View from the top of 22 Bishopsgate facing East on a sunny morning with the top of the Gherkin right in front of us a few meters below. At the back we can observe the Canary Wharf skyline in competition with the changing skyline of the City of London.

Photograph by Antonio Moll.