The 1920s Dymaxion House designed to be an innovative housing solution for American citizens by architect/inventor Richard Buckminster-Fuller

‘Dymaxion’ was a word coined by Richard Buckminster-Fuller in the 1920s to refer to his various design and engineering projects. A portmanteau of the words dynamic, maximum and tension, Buckminster-Fuller designed the Dymaxion Car, the Dymaxion Map as well as the Dymaxion House.

An inventor, engineer, poet and architect, Buckminster-Fuller originally conceived of his transportable, circular, metallic Dymaxion House in the mid to late 1920s. It was not until the housing shortage just after World War II that Buckminster-Fuller, also known as Bucky, found a potential backer willing to fund prototypes of the house.

Dymaxion House design

The purpose of the design was to enable mass-produced houses that were easily transportable to any location in the world. Buckminster-Fuller’s design concept was to be fire-resistant, earthquake-proof and able to withstand extreme winds of up to 180 miles per hour. He wanted the dwelling he was perfecting to be suitable for all location and weather types.

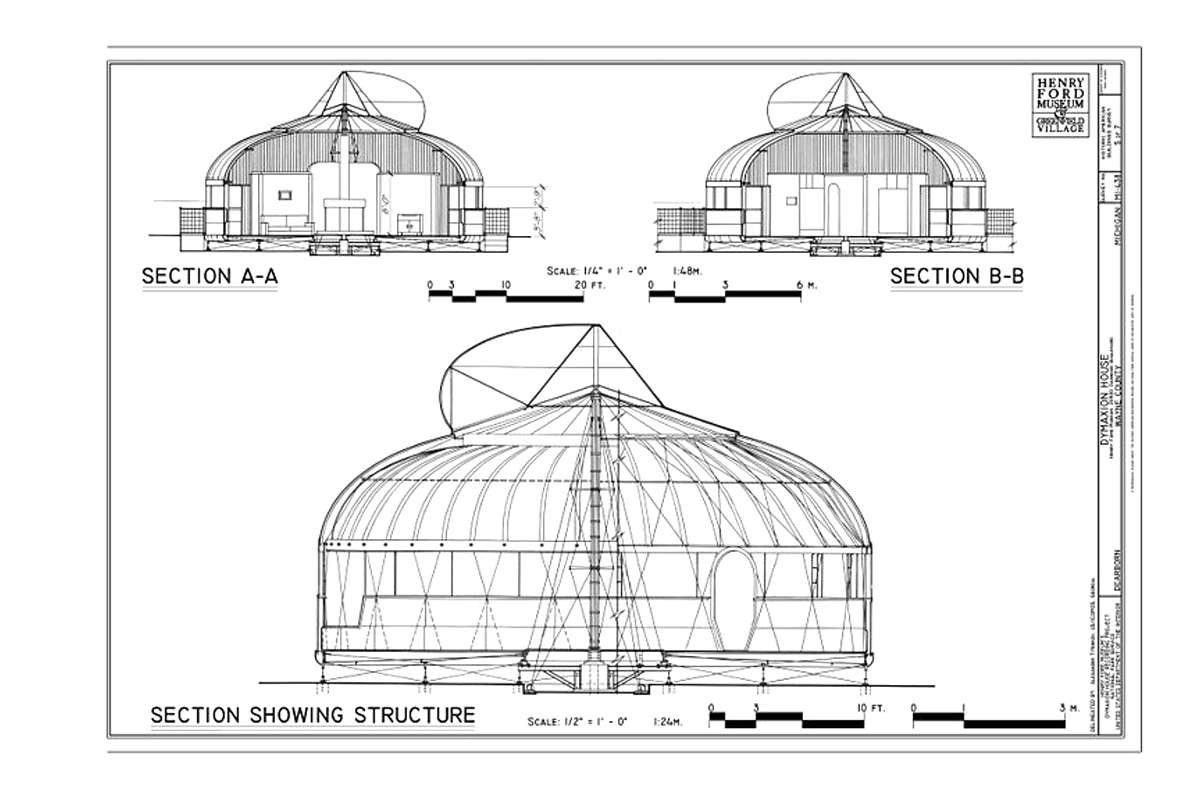

Cross-section drawing of the Dymaxion House, an innovative housing solution first developed by American architect and inventor Richard Buckminster-Fuller in the late 1920s.

Buckminster-Fuller’s lightweight design weighed just 1,360kg or 3,000lbs compared to the average weight of 150 tons for a home at the time in the USA. It used a light, central stainless steel mast or column to give the necessary tension to support the structure. The design also allowed the 1,100ft² house to be erected without the need to use a permanent foundation – you can imagine it as a robust umbrella!

Interior design of the Dymaxion Home

The circular structure contained a living room, two-bedrooms, two bathrooms and a kitchen with the window in the living room an impressive 33ft long. The house had a number of space-saving features including built-in closets that rotated out of the wall and a dustproof hat-rack located behind the bedroom mirror. Other innovations included the ‘O-volving’ shelving system which eliminated any bending down by rotating shelves to the correct level, bringing the clothes or sheets to you.

The interior of the Dymaxion House designed by Richard Buckminster-Fuller on display at the Henry Ford Museum in Michigan. The lounge contained a 33ft long window. Image from the Collections of The Henry Ford Museum.

Buckminster-Fuller also wanted the Dymaxion House to be as environmentally efficient as possible. The house heated and cooled itself by natural means as well as having a compact built-in air conditioner and heater. The house, beautifully fabricated out of aluminium, didn’t require painting and had minimal exterior maintenance needs.

A 1940s version of the Dymaxion House designed by Richard Buckminster-Fuller. He spent many years perfecting his concept for a mass-produced, easily-assembled, resource-efficient home.

Roof of the Dymaxion House

The Dymaxion House had a remarkable revolving roof with an engineered downdraft that meant all the air contained within the building was changed every six minutes. A second advantage of the building’s air-flow was that it blew atmospheric dust downwards towards the skirting boards. The collected dust was then removed from the house via filters which significantly reduced the need for vacuuming.

There was also a greywater system in the roof that collected water for the toilets and a gutter on the inside to collect condensation.

Business plan

Buckminster-Fuller’s business plan was to lease units to buyers or sell each one for the price of a high-end automobile to be paid off over five years. That meant each Dymaxion House would carry a relatively steep price-tag of $6,000, which in 1945 would equate to around $86,000 in today’s prices.

In 1946, Fortune magazine saw a very successful road ahead for the futuristic homes. They described it as ‘a product that would have more significant social consequences than the introduction of the automobile’.

They were wrong. Buckminster-Fuller was too slow in perfecting his designs and only the prototypes ever made it into production. The project’s failure confounded many people who thought these spectacularly innovative dwellings were going to be one of the solutions to the post-war housing shortage.

The Dymaxion House, or the ‘dwelling machine’ as members of the public in 1945 called it, recently finished an extensive eight-year renovation (so much for low maintenance), and this restored unit is on permanent display at the Henry Ford Museum in Michigan.

I think this environmentally friendly, mass-produced housing solution would be more appreciated today. ‘Less is more’ was the philosophy that Buckminster-Fuller lived by which is definitely in tune with today’s global trends.