A virtual tour of Oscar Niemeyer’s Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Niterói, Brazil

The location

Opened in 1996, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Niteroi is one of the smaller, but no less intriguing buildings designed by one of my favourite architects; the famous Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer. A building that reflects his skill of blending sculptural elements with Architecture, the museum designed by Niemeyer with the assistance of structural engineer, Bruno Contarini, is perhaps also one of the best examples of a building that takes intentional advantage of its location on a site imbued with natural beauty. Sitting on the Boa Viagem beach and overlooking the Guanabara bay and the city of Rio De Janeiro, the building is quite dramatic, yet fits in with the natural context and the adjoining residential neighbourhood. Depending on whom is telling the story, Niteroi is a suburb of Rio de Janeiro, municipality of Rio de Janeiro State or an independent city that seats across the Guanabara bay from Rio de Janeiro city.

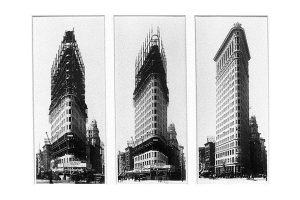

Approaching the building

The full history of this building’s beginnings can be found elsewhere on the web. The focus of interest here is the experience of a visitor to the museum particularly as one walks up the approaching road towards the museum coming off the ferry ride across the Guanabara bay from the Rio de Janeiro side. As one walks up the Avenida Almirante Benjamin Sodre road which curves along the edge of the bay, the full effect of the building as ‘Sculpture’ gradually comes into focus at about 150m from the building’s entrance through a simple gate.

Approaching the Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Niterói, Brazil from the Avenida Almirante Benjamin Sodre.

Photography by Lola Adeokun.

The gateway to the Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Niterói, Brazil from the Avenida Almirante Benjamin Sodre.

Photography by Lola Adeokun.

The simple fencing around the Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Niterói, Brazil looking from the Avenida Almirante Benjamin Sodre.

Photography by Lola Adeokun.

The boundary fence and gate are simple and transparent, allowing the tranquillity of the hilly backdrop and the beauty of the building which has been described as a ‘flower’ by Niemeyer himself, or by others as a ‘goblet’, to be visible from the road. The narrow base or ‘stem’ which supports a wide-rimmed, concrete sculpted, goblet-like upper body seems to defy gravity, yet is rooted in the promontory, allowing views towards the ubiquitous residential blocks which make up much of downtown Rio across the Guanabara bay. Its geometrical dimensions- 16 meters height; accommodates three floors with its upper rim diameter of 50 meters- emphasises its structural daring as well; a tribute to the genius of Contarini too. Niemayer describes the ease with which the design flowed from the configuration of the site itself (translated from the museum website), stating:-

“How easy it is to explain this project! I remember when I went to see the place. The sea, the mountains of the river, a magnificent landscape that I should preserve. And I went up with the building, adopting the circular form which, in my view, the space would require. The study was ready, and a ramp leading the visitors to the museum completed my project”.

The base of the sculptural shape, reminiscent of a goblet. Oscar Niemeyer’s Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Niterói, Brazil.

Photography by Lola Adeokun.

Looking across Guanabara Bay from Oscar Niemeyer’s Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Niterói, Brazil.

Photography by Lola Adeokun

The glazed middle band on the exterior provides successful contrast between the upper wide rim of the building and the narrow stem of the flower or wine goblet and provides much needed views and connection with the exterior from the inside of the building. The building has curved display walls which take you in circular movements within the building and works quite well with the shape of the form, while the sweeping white walls which are shielded from direct sunlight protect the display objects and artefacts from damaging UV rays.

Going inside

The movement from the outside ramp into the interior circular corridor-galleries are like layers of an onion, which then terminate in a central display space which is lit from above. This cleverly takes the visitor from the sunlight into the muted view of the outer layer of the onion with its shaded and uninterrupted views of the bay. The view disappears as one moves round towards the centre in a concentric movement which by taking away the outside views, plunges the visitor into subdued light, focusing the visitor towards the display on the wall, yet the hold of the building form is only slightly relinquished when one arrives in the centre where the roof light brings in light and connection again with the exterior with paintings and graphic works mounted on the curved walls. However, despite the dramatic experiences felt over the years by many, attested to by the recent use of the external forecourt and red ramp for the Louis Vuitton’s Cruise 2017 show, the interior is perhaps less successful for the artworks. The artworks seem to struggle a bit in coming to the fore and are somewhat subservient to the ambience of the building form itself. The exhibition that I visited in this amazing building was quite contemporary, perhaps even risqué, and was certainly able to hold its own in the centre gallery, but I found my experience of the inner long curved galleries less memorable.

Sweeping curved white walls display artwork in Oscar Niemeyer’s Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Niterói, Brazil.

Photography by Lola Adeokun

The play of natural light within the curves and space. Oscar Niemeyer’s Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Niterói, Brazil.

Photography by Lola Adeokun

Perhaps it is a building which contributes significantly to one’s experience of the artistic world as much as the exhibits, but I would suggest that the onus is on the curators to help the artworks find expression alongside the moving expression of the building itself. So, as architecture, do I think the building ‘hits the mark’? Yes, but only if the art curated is equally assertive. The Museu de Arte Contemporânea may be one of Niemeyer’s smaller works- but only in size- it is a bonafide example of why the combination of sculpture meets architecture in my opinion, is worthy of a ferry ride from Rio across the Guanabara bay.

The works of art have to rise to the challenge of a striking building. Oscar Niemeyer’s Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Niterói, Brazil.

Photography by Lola Adeokun

Circular, sweeping interior rooflight. Oscar Niemeyer’s Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Niterói, Brazil.

Photography by Lola Adeokun